Screenshot: Metareality

Bringing African Fables into Games

Dr. Katrina HB Keefer explores how developing the historically-rooted game Bunce Island: Through the Mirror has required an unconventional approach to storytelling. With a narrative set in early eighteenth-century Sierra Leone, understanding and representing complex histories requires accepting folk tales and traditional narratives which are challenging to untangle.

Tracing Folk-Tales in Sierra Leone

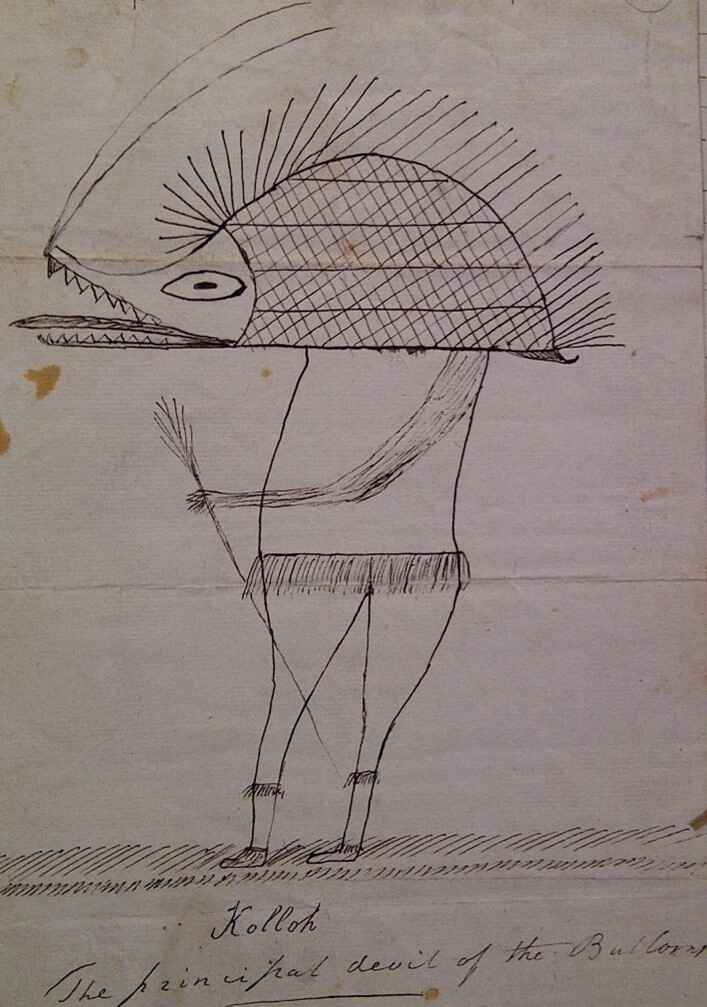

In the first two decades of the nineteenth century, Gustavus Reinhold Nylander, a missionary born in Tallinn (then Revel) who was working on behalf of the English Anglican Church Missionary Society chose to document not only the traditions and cultures of the Bullom people he lived among but to record their folk tales. Nylander had been stationed on the so-called Bullom Shore opposite the fledgling colony of Sierra Leone and its central settlement of Freetown. He established a small mission which was named Yongroo Pomoh, or “Little Yongroo” due to its relative closeness to Yongroo, the heart of the Bullom kingdom. Nylander is remembered by modern scholars for his startlingly objective descriptions of the cultural traditions he observed and described in his copious correspondence.[1] He proved a poor evangelist but an excellent amateur ethnographer, drawing initiatory society masquerades and elaborating on the complexities of the power structure of the region.

Perhaps the most important evidence Nylander leaves modern scholars is one of the least studied: he transcribed three Bullom folk tales into his 1814 publication Grammar and Vocabulary of the Bullom Language as examples of syntax. These represent a precolonial snapshot of legends and folk histories captured by a man who from his other efforts was intent on describing what he heard and saw without significant bias. This point is an important one to which we will return.

The first fable which Nylander presents concerns an exchange between a lion, a goat, and an elephant. He states that they were told to him by a Bullom informant, whom Nylander does not name. The second tale which Nylander provides concerns a chameleon, a monkey, and the palm-wine-maker.

The chameleon and the monkey were gone to visiting, and met with the wine of Sighno. Monkey said, Friend, let us drink it. Chameleon replied, I am not bold enough. Monkey said: Puh! let us drink it. Chameleon said: Go thou drink it. He climbed up, and drank plenty and came down; and they went on. The owner of the wine walked after them, and saw the wet footsteps; he followed them quickly and overtook them, and asked, saying; Who is he that drank my wine? The monkey said: I am not he. The chameleon denied it. Monkey said: As it is denied in this way, look at us – he that staggers, the same is he (that) drank it; and he walked, he stood still, and said: Look, do I stagger? He said to the chameleon: Thou also shouldst walk if thou art not drunk. He passed, and he stood still; he staggered. The monkey said: See! the wine – drinker is not hidden. The man took hold of the chameleon and beat him much, and dismissed him, and said: I forgive thee for monkey’s sake; or, if it were not for the sake of the monkey I would kill thee; (or, it is for the monkey’s sake I do not kill thee.) but They went forward, and met a farm prepared for burning . The chameleon said; Let us burn the farm. The monkey replied: Aye! I won’t. The chameleon said: Stay! let us burn it; he went and took a firebrand, and kindled the fire; it burnt until dead – it extinguished. The people came and inquired about it. The chameleon said: I do not know, I saw the smoke, but I entered not hands there. The monkey said: I also (viz . innocent). The chameleon said: As he thus denies it, only look at our hands, the burner of the bush cannot be hid. The chameleon’s hands were examined, and found to be clean, and he said: Stretch out the monkey’s hands. As the monkey stretched out, they looked as if they were black; he was taken hold of, and they beat him and struck him with a blow, that left his head short, and entered into the woods.

The final folk tale concerns a caterpillar and a tortoise who face famine and trick one another. Each of these tales seems to illustrate cultural norms and traditions which were deemed important to early nineteenth-century Bullom in the precolonial upper Guinea coast. They feature species which were all present in the region and there are clearly trickster characters in the stories. There are elements of culture present – the palm-wine maker, the cultivation of farms, memories of famine and more. These tales are of course not rooted concretely in any archaeology, nor in a clearly articulated historical chronology. These animals cannot converse in the real world, and rather exist where all such fabulous beasts do: in our shared imagination. Analyzing this type of oral tradition is the purview of folklorists and some anthropologists, and while meanings can certainly be extracted, relating them to reality can be difficult.

Building a game-world

Constructing an authentic and carefully researched game environment which is anchored in real historical spaces and actual landscapes demands a rigorous meticulousness to the designer’s approach. In the example of Bunce Island: Through the Mirror, there are layers of detail which demand attention and care. Beginning with the GIS and satellite data from which the complex topography is built and followed by lengthy interviews with those familiar with the archaeological site, my team and I sculpted the island on which the slave fort ruins remain. Multiple site visits and hours of effort went into checking and cross-checking the location of the actual digitized buildings we constructed against the site surveys, followed by further meetings with archaeologists who have worked on the island for decades. Every tree’s placement was considered against a plethora of photographs taken over time to ensure that every possible element of accuracy would be present.

Working in the Unreal Engine, I used a flat plane with an overlay of the most reliable survey map to ensure high fidelity placement of structures in relation to one another and approached all foliage in much the same way. Every aspect was checked for factual accuracy. For the purposes of simply digitizing a real-world space to the highest degree of authenticity, this approach is a good one. But for an engaging game to be developed which captured the past, and particularly the precolonial part of Sierra Leone, this approach simply isn’t enough.

Sierra Leonean history has been curated for decades by outsiders. As one of the first British colonies in Africa, and indeed, the administrative heart of British West Africa as a whole, Sierra Leone bore the brunt of English colonial aspirations and efforts. Settled by Black Loyalists from Nova Scotia, Canada, followed by Jamaican Maroons, and then by waves of enslaved Africans “liberated” from slave ships captured by the British West Africa Squadron of the Royal Navy between 1808-1862, Sierra Leone was a cultural melting pot and a focal point for empire. Culturally, there was a clear distinction between the Colony (the Freetown peninsula extending down to Sherbro Island) and what was later forcibly acquired as the Protectorate (the interior, made up of various Islamic kingdoms, powerful sociolinguistic groups of cities, or decentralized regions). The latter was not well studied during the nineteenth century, and certainly, study would have been a complex matter even without all the trappings of Victorian arrogance and nascent imperial ambition.

Screenshots: Metareality

Game worlds, authenticity, and secrets

The primary connection between all the diverse peoples beyond the colonial boundaries was a complicated and interwoven group of initiatory societies which to this day remain vitally important in preserving culture and regulating aspects of life throughout the country. The best known of the many societies are the gender-defining Poro and Sande Societies, which govern the transition into adulthood of male and female children in the 16 distinct participatory ethnic groups regionally. Due to the importance of secrets in these societies, discerning deeper truths and understanding historical traditions becomes a truly fraught process. Making the process even more challenging is the relationship between symbolism, secrecy, and fact within the cultural consciousness of many regional groups. Among many of the Mande-descended peoples, as Ferme has described, knowledge – particularly knowledge held by hunters – is only offered to the worthy, and tends to be shrouded in layered metaphors which must be parsed gradually. She relates a story of a hunter who delighted in leading his rapt Mende audience through a complex story which unfolded with the same diligent care as an actual hunt. This, Ferme writes, is “deep Mende,” an esoteric way of telling tales which relies on multiple degrees of “knowing” among an audience.[1] In this way of telling and seeing, the forest must be “read” and interpreted. Stories become complex and meaningful, with trickster characters and shapeshifters, witches and spirits. One character in the Mende people’s shared tradition is the Ndͻgbͻsui, a shapeshifter which can only be escaped if the intended victim can dissimulate and tell about daily life in its precise opposite. Thus if asked how one carries water for example, the putative victim must answer “with a fishing net” to survive.[2]

When one steps beyond the concrete safety of archaeological ruins, surveys, and GIS data, one discovers a murky and complicated landscape of stories which are not well described thanks to the desires of the late nineteenth century colonists to “civilize” what they deemed as savage. Cultural anthropologists since the 1960s have lived among various groups in present-day Sierra Leone and recorded and interpreted what they can, but these must be understood to have been filtered through colonization over centuries. Scholars like Rosalind Shaw, who lived among the Temne people in the late 1970s, listened to diviners as they told stories of a complex world peopled by witches and spiritual beings. Ritual Closing of homes, bodies and souls against attack was described to her, particularly the Darkness medicine (ka-woso in Temne) which serves to muddle the spiritual eye and confuse would-be attackers.[3] Stories which Shaw collected from her informants described past worlds which had existed before this one, but which had ended in death and annihilation. Pa Kaper Bana’s story of this history is recorded by her, noting that “the first world in the old days, it was an angry world.”[4] For Shaw, this is a memory of the violence of the trans-Atlantic slave trade, which was encoded into the landscape and memories of the people with whom she worked. When she asked about the ending of the First World, she was told that

It was taken and turned over. The first things, all the bad ones, they were pressed underneath. He (K-uru) started again, a new world. The people of the older days were short, short, short, short! They were the ones who disappeared, yɛn! The first people, those short people, they came and troubled the world. That was why K-uru turned them over. He made a new world again.[5]

These stories which anthropologists have collected demonstrate a complex engagement with the past. The worlds through which the peoples of the interior navigated in the precolonial period were ambiguous, shaped by spiritual forces and entities, and described with symbolic and layered fables.[6]

Ethics and development

Returning to Nylander’s remarkable trio of fables, we could likely begin to parse these stories in similar ways to how Shaw and Ferme worked to discern and interpret meanings in the folktales they were exposed to. And for the purposes of scholarly interpretation that would likely be important and significant. But what about developing a game world? How do we shape a digital past which is peopled by shapeshifters, tricksters and spirits? Importantly, how do we gauge what can and cannot be shared or told? Ultimately, the only reasonable and ethical approach is one which respects the right of peoples to tell their own stories, and to layer complex meanings as they deem appropriate. Community collaboration and coauthorship become key and have been the core of development for Bunce Island: Through the Mirror. If community members share a story which they wish included, our team has committed to its inclusion without hesitation, and to removal of any aspect of the game world which is deemed unworthy, no matter how historical it may have been deemed. The land will be peopled with Ndͻgbͻsui and rituals will be made real, with the same respect given to these cultural narratives drawn from folk tales as to European-derived game worlds.

Notes

- 1. William A. Hart, “A West African Masquerade in 1815,” Journal of Religion in Africa 23, 2 (1993): 136-146; Katrina HB Keefer „The First Missionaries of The Church Missionary Society in Sierra Leone, 1804–1816“ History in Africa 44 (2017): 199-235.

- 2. Mariane C. Ferme, The Underneath of Things: Violence, History and the Everyday in Sierra Leone. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001. 31-32.

- 3. Ferme, The Underneath of Things, 32.

- 4. Rosalind Shaw, Memories of the Slave Trade: Ritual and the Historical Imagination in Sierra Leone. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002. 60-61.

- 5. Shaw, Memories of the Slave Trade, 64.

- 6. Shaw, Memories of the Slave Trade, 65.