Digital Death

In her curatorial exploration, Stacey Pitsillides highlights the spectrum of experimentation in online memorialisation and its complex dynamic between the deceased and their role in the lives of the living. Through five paradigmatic initiatives, she showcased the evolving digital mourning landscape and explores forms of digital immortality.

Memorialisation VS. Reanimation

Text: Stacey Pitsillides

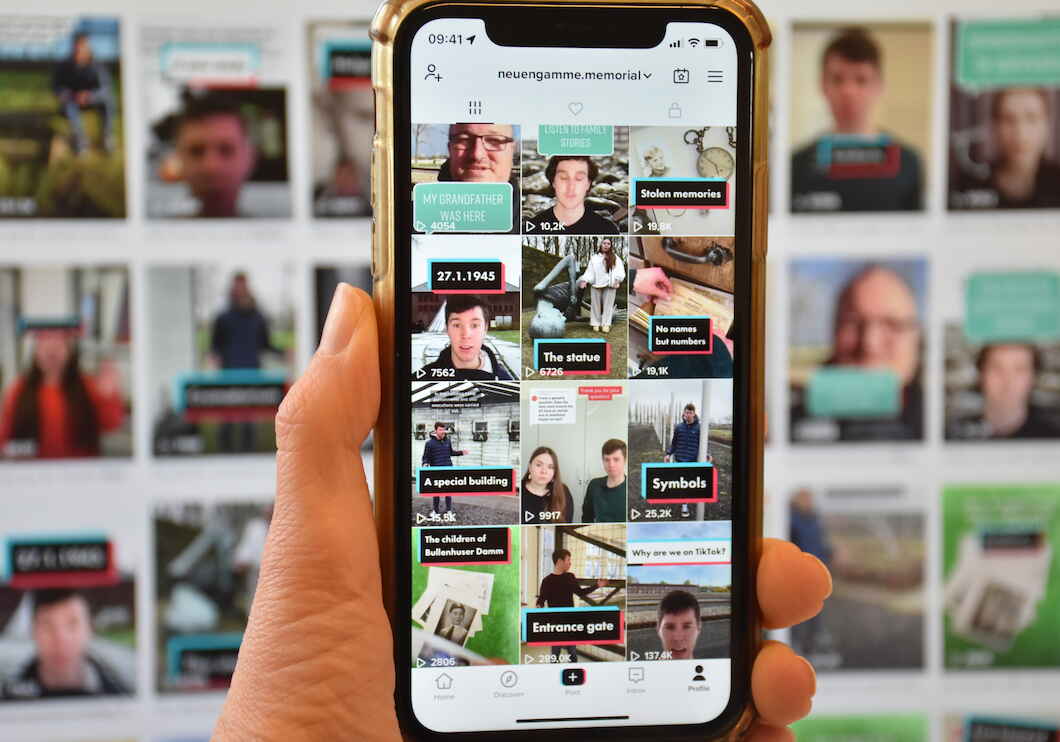

In the 21st century digital technology has been appropriated, designed and re-designed to integrate death and grieving into everyday life. These practices have been further normalised since the Covid-19 pandemic. Online memorialisation is perhaps one of the most recognized of these. These memorials are now an established part of building community between bereaved persons and for continued interactions with the dead.

Alongside this, there is a growth of innovators whose quest is to reanimate digital versions of the self – for immortality or posterity. This article aims to hold space between traditional uses of technology for the preservation of memory and memorialisation, to more experimental approaches where we interact with the dead in games, through bots or VR, into dreams of science fiction authors and technologists who wish to create new digital humans or posthumans.

Memorialisation practices have always been interwoven with new technology and often play with boundaries of the agency of the dead and their role in the lives of the living

Memorialisation gives permission for public expressions of grief that, historically, were socially hidden along with enfranchising otherwise illegitimate loss. It also supports the creation of social norms and netiquette. Memorialisation practices have always been interwoven with new technology and often play with boundaries of the agency of the dead and their role in the lives of the living, e.g. spirit photography popularised in the 1800s often captured images of ghosts interacting with other human subjects.

When the World Wide Web was created in the 1990s online memorials soon followed, shifting from simple image and text-based guest books to our current media. For example, one of the earliest virtual memorial gardens launched in 1995, was the World Wide Cemetery. Social media are often the primary site of today’s memorials with platforms such as Facebook, Instagram and Twitter (X) creating new avenues for digital storytelling and talking to the dead.

Unfinished Farewell – Politics of Memorialisation

During the global pandemic, China became the site of the first cluster of COVID-19 cases (Dec 2019) and their subsequent global (often digital) memorialisation. A prominent example of social media memorialisation is Dr Li Wenliang, the Wuhan doctor who became known as the COVID-19 whistle-blower. His Sina Weibo1 account swiftly became a virtual space for shared commemoration, conversation and critique, likened by the media to a Wailing Wall. It strikes a balance between grief, political commentary, and everyday encounters e.g. the doctor’s love of fried chicken.

The politics of memorialisation is well documented, but the COVID-19 pandemic gave designers and technologists the space and desire to create unique places to commemorate the dead. This includes Unfinished Farewell which references the political nature of memorialising COVID-19 deaths, as people in China were removed from the formal death toll to keep numbers low, so the site acts both as a memorial and evidence of this era.